Are Scaling Laws Really Plateauing?

We’ve all seen the charts: as you increase model/dataset size, test error (used to measure performance) decreases following a seemingly predictable curve (e.g. Kaplan et al. (2020) and Hoffmann et al. (2022)). At some point, the curve flattens, and people start talking about “plateaus” in scaling laws—implying we’ve reached some fundamental limit.

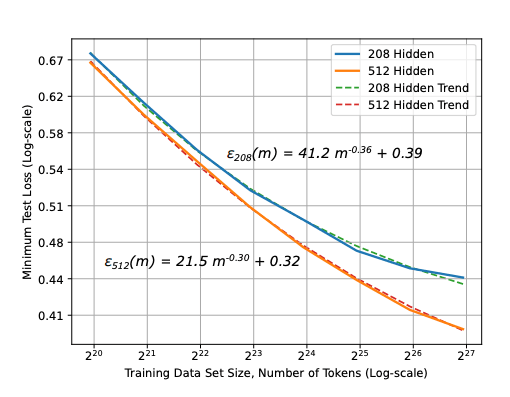

In this blog post, I will focus on Data Scaling laws, simple rules that describe how performance improves as we feed more data into a model. Researchers (mostly in industry, where such experiments are feasible) often report that error decreases at a certain rate, something like , where is the number of training samples (e.g. tokens in the case of language models). Scaling laws look like this:

However, such scaling laws are established in a very specific setting: the model is fixed (and only width/depth etc are scaled), the dataset is fixed as well and only the number of training samples is scaled (from a fixed dataset), the parameterization of the hyperparameters (learning rate, batch size, etc.) is fixed (e.g. the same learning rate is used for all layers in the MLP block). With this, it is natural to ask: are the observed plateaus real fundamental limits or the result of suboptimal scaling? (here, suboptimal should be understood both in terms of asymptotic performance and the scaling rate).

In this post, I’ll show through a simple example that the scaling laws we see depend heavily on how we use the data and the quality of the data itself. With different data selection strategies—even starting from the same underlying distribution—we can end up with different scaling rates and different asymptotic performance. This suggests that before concluding we’ve hit a true plateau, we need to understand what the optimal scaling laws could be. Without that, “plateauing” might be less about nature’s hard limit and more about our current suboptimal approach to learning at scale. While theorists (especially statisticians) might be familiar with this, I think it is important to highlight this point to practitioners.

I. Scaling Laws depend on Data Strategies

Consider a simple linear model:

We fit a slope via ordinary least squares (OLS) without an intercept:

The solution to this problem is given by

and the test error is given by

We will see that under the full, ideal usage of data, converges to at a rate . But if we restrict or filter our data in certain ways, that rate can worsen, or improve.

1. Scenario A: Full-Range. In this case, we assume that training data is drawn from the true distribution.

Training Data: i.i.d. from .

Standard OLS results shows that converges to at a rate , which yields the following scaling law:

- converges to at a rate .

2. Scenario B: Samples Near Zero. Here, we assume that the data collection process is imperfect, and we only have access to samples with small norms.

Training Data: samples with small, e.g. where as .

In this case, the slope signal is small, so has a high variance, which naturally slows down the convergence rate. More precisely, we have:

As a result, we have a slower scaling law:

- converges to at a rate .

3. Scenario C: Select Low-Noise Samples (). Here, we assume that we have access to a verifier that can select low noise samples, i.e. samples for which is small, effectively lowering the noise in training.

Training Data: low noise samples, i..e samples for which is small. The variance of might shrink faster than . This is straightforward to see:

where is the effective noise level in the training data. The final test error remains . However, if we can use the verifier to select low-noise samples, we can speed up the convergence rate. For instance, if we can select for some , we have:

- converges to at a rate .

Key Takeaway

Even though the true process is the same, the way we use or filter the data can drastically alter the scaling law---how quickly converges to 1. Some strategies slow down learning (Scenario B), while others can speed it up (Scenario C).

II. Asymptotic Performance depends on Data Quality

To show the impact of training data quality on asymptotic performance, we consider a linear model with a bias term that we don’t model. Specifically, suppose the true data is coming from the following model:

where is a fixed bias term, and is Gaussian noise, and the input is drawn from .

We fit a model of the form (ignoring the bias). This introduces an irreducible error in the model. By minimizing the mean squared error on the training data, we find the optimal parameter :

As increases, converges to . The asymptotic test error is given by:

We will now consider four scenarios that differ in how they use the data, and see how they affect the asymptotic performance.

1. Scenario A (Full-Range): In this case, the training inputs are drawn uniformly from , which covers the entire input space.

In this case, we have . The test error approaches the asymptotic limit .

2. Scenario B (): Assume that for some reason, we only have acces to training samples satisfying , which introduces a bias in the training data distribution. In real life scenarios, this represents the case where the training data does not cover all the input space (of the true data distribution). This changes the asymptotic solution to:

The asymptotic test error becomes:

where accounts for the bias introduced by using only half the support of , and the final test error is worse than in Scenario 1.

III. What Does This Mean for "Plateauing" Scaling Laws?

In the scenarios above, the underlying data distribution is identical. Yet, the test errors and the scaling laws are different:

- Different scaling rates (, , etc.).

- Different asymptotic limits ( vs. ).

This demonstrates that the way we use/select data—not just the data itself—can significantly impact both the scaling law and the best achievable performance.

IV. Beyond Simple Models: Implications for Large-Scale Models

For large language models and other neural networks, scaling laws are often treated as fixed. But as these examples show, they are highly dependent on data strategies. The impact of data quality was studied through the lense of data pruning (see Sorscher et al. (2022) where authors studided the impact of data pruning on scaling laws, and our paper Ayed et al. (2023) for a detailed analysis on the impact of the quality of data selection on scaling laws). While this blog post focused on data scaling laws, the same principles apply to other scaling laws, such as model scaling laws.

If we rely on suboptimal scaling strategies, we might misinterpret observed plateaus as fundamental limitations. In reality, they could reflect missed opportunities to optimize scaling strategies. Before concluding that a scaling law has plateaued, we need to ask: is this the best possible scaling law? is the model/dataset parameterization optimal? Without knowing what the optimal scaling law looks like, it’s premature to assume that any observed behavior reflects a true limit rather than a shortcoming in our approach.

References

Hestness, J. et al. Deep learning scaling is predictable, empirically. (2017).

Kaplan, J. et al. Scaling laws for neural language models. (2020).

Rosenfeld, J. et al. A constructive prediction of the future of scaling laws in machine learning. (2020).

Sorscher, B. et al. Beyond neural scaling laws: beating power law scaling via data pruning. (2023).

Ayed, F. et al. Data pruning and neural scaling laws: fundamental limitations of score-based algorithms. (2023).